a common culprit with uncommon presentation

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D3484966z2Main Content

Phthiriasis Palpebrarum: A common culprit with uncommon presentation

James Pinckney II MD1, Patrick Cole MD2, Sangita Patel Vadapalli OD3, Ted Rosen MD1

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (4): 7

1. Department of Dermatology2. Department of Plastic Surgery

3. Department of Ophthalmology

Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. vampireted@aol.com

Abstract

Since infestation of the eyelashes by pubic lice is relatively uncommon, it might well be misdiagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis, allergic contact dermatitis, or seborrheic and rosacea blepharitis. We present and graphically illustrate a case of blepharoconjunctivits attributed to P. Pubis infestation and offer further support for the use of the ophthalmologic agent 4 percent pilocarpine gel as a primary or adjunctive treatment modality.

Introduction

Although Phthirus pubis is frequently found in the hair of pubic, rectal, and inguinal areas, infestation of the eyelashes is relatively uncommon and rarely encountered by dermatologists. Thus, it is probably misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated in some cases. For example, bacterial conjunctivitis, allergic contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and rosacea blepharitis might be confused with phthiriasis palpebrarum. Although phthiriasis may be acquired via close contact with an infested person or by contaminated clothing, towels and bedding, transmission is typically the result of sexual activity. Importantly, evidence of P. pubis infestation may indicate sexual abuse in children or sexual activity in adolescents. We herein present the case of an adult male found to have blepharoconjunctivits due to P. pubis infestation and offer further support for an emerging treatment for this manifestation of louse infection.

Clinical synopsis

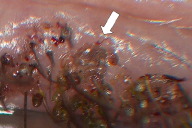

A 53-year-old man presented with chief complaints of severe itching, irritation, and gritty sensation in both eyes of 3 months duration. Past medical history disclosed that his granddaughter had "head lice" several months prior and that the infestation was allegedly contracted at her daycare center. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed a visual acuity (with correction) of 20/25-2 in the right eye and 20/20-1 in the left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed extensive nits and pinpoint blood-tinged debris along the superior and inferior eyelid margins of both eyes. Adult lice were also visualized embedded into the lid margin. The nits were strongly adherent and appeared to encase virtually every eyelash. (Figs. 1 & 2) Numerous eggs were also visible along both eyelids. The cornea and conjunctiva were unremarkable in both eyes, as was the remainder of the eye examination. Based upon the finding of nits, eggs and adults, the diagnosis of phthiriasis palpebrarum was made. The patient was instructed to apply a liberal amount of bacitracin ointment to his eyelid margins twice daily to be alternated with 4 percent pilocarpine gel twice daily for 10 days. Due to the severity of the nit deposition along each eyelash, manual forceps removal was not attempted. An extensive discussion with the patient regarding the etiology of his condition as well as the importance of strict personal hygiene was performed. Two weeks following initial presentation, all evidence of phthiriasis was gone.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Innumerable nits coating eyelashes (slit lamp exam) Figure 2. An embedded adult louse (arrow) along with numerous nits | |

The patient was referred to his primary care physician the day he first presented for testing for additional sexually transmitted diseases, inspection of non-ophthalmologic hair bearing areas for lice infestation, and additional topical treatment, as appropriate. A report obtained subsequently indicated that the patient also tested positive for chlamydial urethritis (for which he received oral doxycycline therapy) and that mild phthiriasis of the inguino-crural area was treated with permethrin application.

Discussion

Although the small, crab-legged P. pubis commonly affects pubic, axillary, or chest hair, involvement of the eyelash and eyelids area is less commonly encountered. Clinically, patients may present with persistent erythema and pruritus of eyelid margins and scleral surfaces along with accumulation of debris along the base of eyelashes. On dermatologic examination, the adult P. pubis may be observed clinging to eyelashes or even buried within the free lid margin. As a result of a semi-transparent nature and ability to rapidly burrow into the lid margin, P. pubis can be easily missed when the eye is involved. Translucent egg structures (nits) are found adherent to eyelash or eyebrow hairs. In addition to a thorough examination of the face, patients must also be inspected for infestation in other hair-bearing areas; patients must also be evaluated for presence of concomitant sexually transmissible disease [1, 2, 3]. Importantly, although pre-pubertal children with phthiriasis palpebrarum are usually infested by direct contact with a parent or shared fomites, sexual abuse must be thoroughly ruled out.

On microscopic examination, the blood-sucking P. pubis has a broad, flattened body that lengthens to 2 mm in adulthood. The wingless, adult louse has 3 separate sets of legs attached to the anterior abdomen. The most anterior pair of legs is slender, with fine claws and a serrated surface, allowing for traction (and mobility) on even glabrous skin [4]. Posterior sets of legs are increasingly thick for improved grasp of hair shafts during sleep and attachment of eggs [4]. While firmly grasping host hair shafts, females may lay up to 3 eggs each day. With an incubation period of 7-10 days, eggs may be visible to the naked eye as 0.5 mm, brown-opalescent ovals. Cemented to the hair shaft, chitin egg cases contain areopyles that allow air to directly contact the developing, internal egg. Multiple tactile septae protrude from the head, legs, and dorsum, allowing P. pubis to sense its environment. Although the average life span of P. pubis may be as long as 1 month, death occurs within 48 hours following removal from the host [5].

The treatment of blepharoconjunctivitis resulting from P. pubis can be challenging. Patients must launder all bedding, clothing, towels and washcloths, all of which may harbor adult lice and their eggs. Temperatures exceeding 131°F for more than 5 minutes will eradicate all viable eggs, nymphs, and adult lice. Because P. pubis eggs may incubate for up to 10 days, careful sealing of all potentially contaminated fabric materials in air-tight plastic bags for 2 weeks must coincide with medical attempts at eradication.

Manual removal of visible lice and eggs with a forceps is standard therapy. Alternatively, eyelashes may be extracted in their entirety [6]. Full removal of eyelashes is followed by complete regrowth in 3-4 weeks. However, such mechanical efforts are quite tedious and may be hindered by low patient tolerance and the firm adherence of eggs to eyelash structures.

Alternative management strategies are legion, but all may have prohibitive adverse effects or present technical difficulties. A time-honored therapy, application of 1 percent yellow mercuric oxide, at a dose frequency of 4 times daily for 14 days, often requires impressive patient compliance for effective treatment [7]. In addition, this treatment may be accompanied by chemical blepharitis, conjunctivitis, lens discoloration, tearing, and photophobia [8]. The agent is also difficult to obtain. Cryotherapy or argon laser phototherapy may allow destruction of ectoparasites but are both associated with discomfort and risk of ocular injury [9, 10]. Both safety and efficiacy are highly operator dependent. Topical application of gamma-benzene hexachloride may be employed; however previous reports link use to ocular irritation and potential neurotoxic effect [1, 11]. "Smothering" lice by twice daily application of plain white petrolatum may be efficacious, but is not ovicidal and thereby risks incomplete therapy [12]. Topical malathion solution 0.5 percent or 1 percent shampoo may be effective after just a few applications, but it is neither approved nor entirely proven safe for ocular use [13, 14]. Although oral ivermectin (250mcg/kg; two doses given at one week interval) appears to be an attractive option, there is only scant published evidence of its efficacy, and it is not approved for this indication [15]. Because many cases of ocular phthiriasis occur in children, the relative contraindication for administration to pediatric patients under 15kg body mass adds an additional complication to the use of this agent.

Although the exact mechanism of pilocarpine 4 percent gel remains unclear, previous studies report effective P. pubis clearance without adverse events following such application [16, 17]. Speculation on the mechanism of action includes an anticholinergic induction of louse paralysis via neuronal depolarization or a direct pediculocidal action [16, 17]. From a pragmatic standpoint, pilocarpine gel is inexpensive, readily available, and approved for direct ocular use. In the present case, the application of pilocarpine gel in combination with a bland ointment quickly terminated visible infestation and presented no untoward effect.

Although infestation with P. pubis may be a common clinical occurrence, blepharoconjunctivitis resulting from the crab louse is rare. It is imperative that the astute dermatologist be cognizant of this entity in order to establish the correct diagnosis and provide timely, safe and optimal management.

References

1. Burns DA. The treatment of Phthirus pubis infestation of the eyelashes. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:741-43 PubMed2. Pierzchlaski JL, Bretl DA, Matson SC. Phthirus pubis as a predictor of Chlamydia infections in adolescents. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:331-34. PubMed

3. Thappa DM, Karthikeyan K, Jeevankumar B. Phthiriasis palpebrarum. Postgrad Med J 2003; 79:102. PubMed

4. Burkhart CG, Burkhart CN. Oral ivermectin for Phthirus pubis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:1037. PubMed

5. Nuttall GHF. The biology of Phthirus pubis. Parasitology. 1918;10383-405. [No UI number available]

6. Yoon KC, Park HY, Seo MS, Park YG. Mechanical treatment of phthiriasis palpebrarum. Korean J Ophthalmol 2003;17:71-3. PubMed

7. Ashkenazi I, Desatnik HR, Abraham FA. Yellow mercuric oxide: a treatment of choice for phthiriasis palpebrarum. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991 Jun;75(6):356-8. PubMed

8. Kestoon BM. Conjunctivitis and blepharitis due to yellow mercuric oxide. Arch Ophthalmol 1931;6:581-82. [No UI number available]

9. Awan KJ. Cryotherapy in phthiriasis palpebrarum. Am J Ophthalmol 1977;83:906-07. PubMed

10. Awan KJ. Argon laser phototherapy of phthiriasis palpebrarum. Ophthalmic Surg 1986;17:813-14. PubMed

11. Wooltorton E. Concerns over lindane treatment for scabies and lice. CMAJ 2003;l68:1447-48. PubMed

12. Orkin M, Epstein E, Maibach HI. Treatment of today's scabies and pediculosis. JAMA 1976;236:1136-39. PubMed

13. Rundle PA, Hughe DS. Phthirus pubis infestation of the eyelids. Br J Ophthalmol 1993;77:815-16. PubMed

14. Vandeweghe K, Zeyen P. Phthiriasis palpebrarum: 2 case reports. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 2006;300:27-33. PubMed

15. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Oral ivermectin for phthiriasis palpebrum. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:134-35. PubMed

16. Kumar N, Dong B, Jenkins C. Pubic lice effectively treated with Pilogel. Eye. 2003 17:538-39. PubMed

17. Oguz H, Kilic A. Eyelid infection. Ophthalmology 2006;113:1891. PubMed

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal